The Race That Broke the Limits:

Inside the Most Punishing One-Day Running Event Ever Conceived

Five races. Thirty-three miles. One impossible question: Who is the best all-around runner in the world?

I wrote about the Original Ultimate Runner Competition years ago. Still, I've never told the full story—the physiological details, the deeper motivations, the moments I've carried with me for nearly four decades in one story. This is that story.

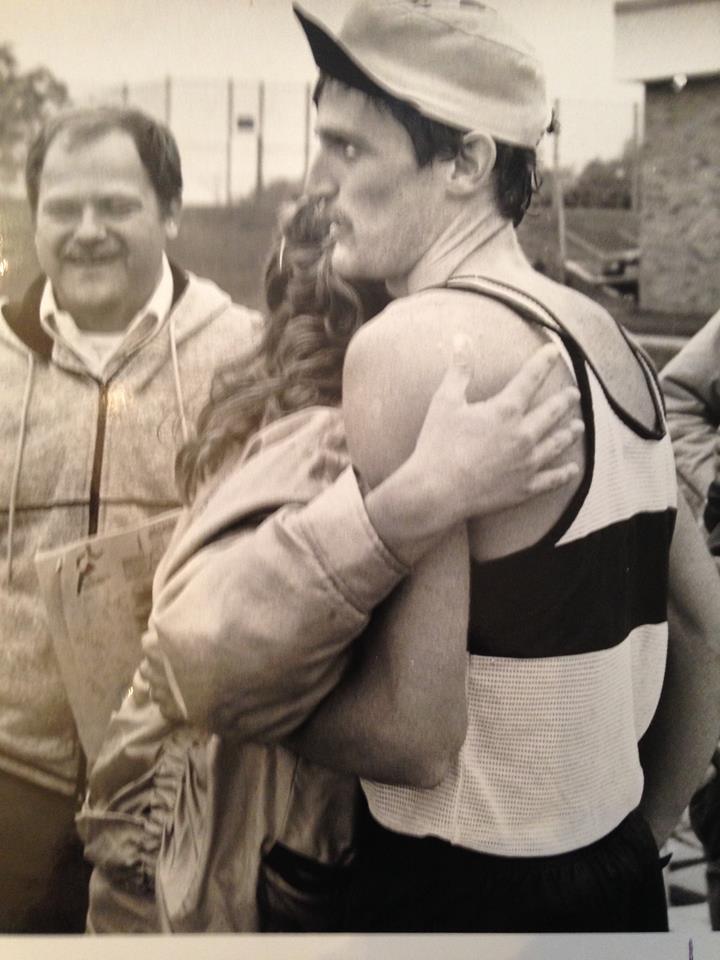

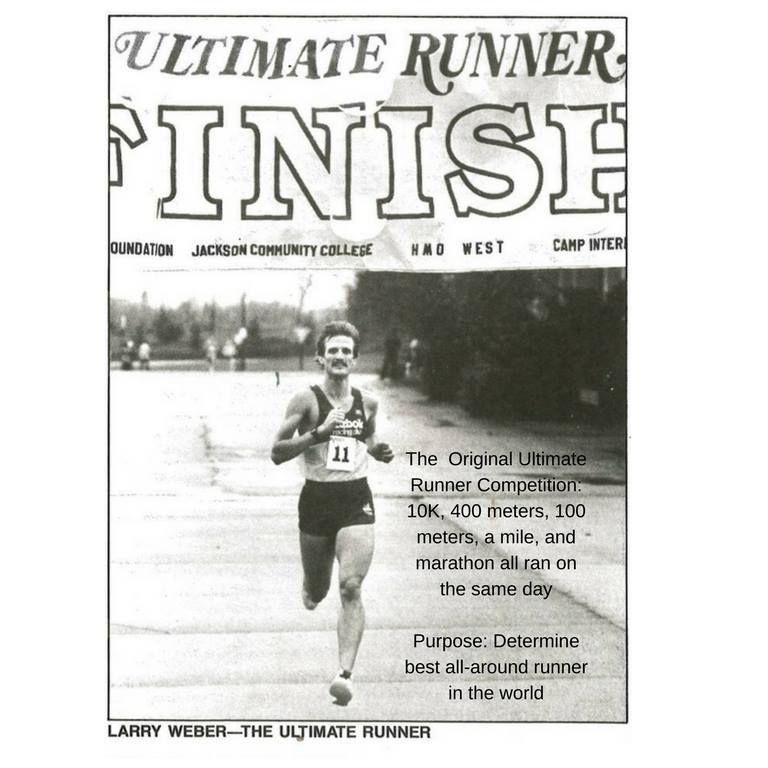

The hug that mattered more than the medal. Just before being physically lifted onto the awards platform after this picture was taken because my legs wouldn't work, I found the young family member with cystic fibrosis I'd been running for that day, and her sister. This moment—more than any record or title—was my why for competing that day.

When the race officials tried to call me to the awards platform, my legs wouldn't respond.

Not fatigued. Not cramping. Non-functional.

They had to physically lift me—like moving a piece of furniture—and place me on the stage. I'd just been crowned "The Ultimate Runner" and best all-around runner in the world by one definition, but I couldn't support my own body weight.

That day turned out to be quite memorable for me, and I managed to achieve a point total that remained unmatched in the event's history.

Olympic marathoner Don Kardong, who competed in the Ultimate Runner a different year, would later say about his own fifth-place finish: "I thought the roadkill looked better than I felt."

Jeff Galloway—another Olympian and renowned running author who ran the event in yet another year—put it even more bluntly: "I haven't had this much fun since Vietnam."

This was the Original Ultimate Runner Competition—and from a physiological standpoint, it was one of the toughest one-day running events ever created.

The Impossible Question

The year was 1985, and the running community had been debating a question for decades: Who deserves the title of best all-around runner?

Is it the miler, combining speed and strength in perfect balance? The marathoner, testing the limits of human endurance? The sprinter, with their explosive power? The ultrarunner, pushing beyond what most consider possible?

Everyone had an opinion. Everyone claimed their specialty represented the pinnacle.

The Ultimate Runner Competition would finally settle it.

The format was diabolical in its simplicity: Run five races in one day—a 10K, 400 meters, 100 meters, a mile, and a marathon. Your score is cumulative based on placement in each event. The highest total score wins like a decathlon.

No room for specialization. No hiding weaknesses. The champion would have to sprint like a 400-meter specialist, endure like a marathoner, and push VO₂ max like a miler—all within hours of each other.

Runner's World magazine writer Jim Harmon, who covered the race one year, called it "the last word in endurance running."

Looking at the carnage it left in its wake—Olympians who said once was enough, elite runners who couldn't stand afterward, world-class athletes comparing it to combat—he wasn't exaggerating.

The Field

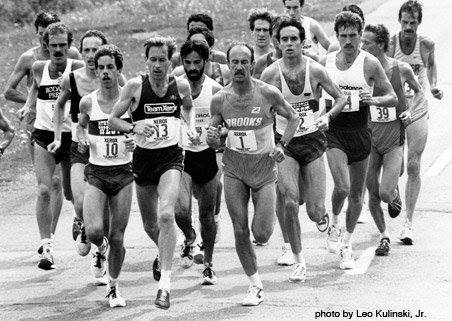

The competitors who gathered in Jackson, Michigan, that day represented the elite of distance running:

Barney Klecker—American record holder at 50 miles, a mark that would stand for nearly 40 years. His son Joe would later make the 2021 Olympic team in the 10,000 meters.

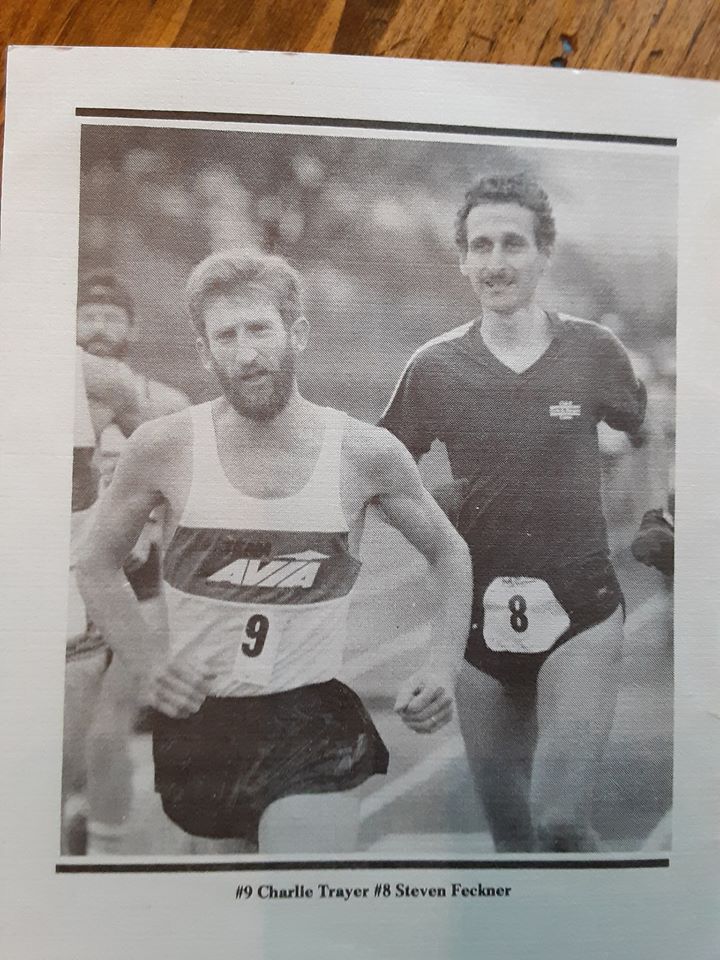

Charlie Trayer—the world's third-ranked ultramarathon runner, later named Ultra Runner of the Year and inducted into the Ultrarunning Hall of Fame.

Stefan Feckner—1988 Ultra Runner of the Year, another Hall of Fame inductee.

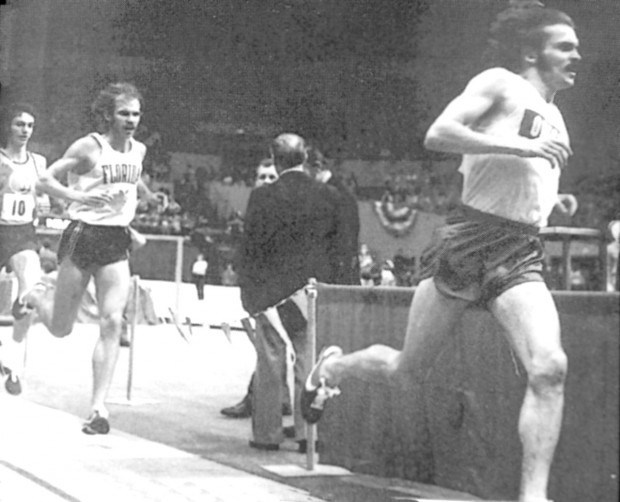

John Craig—thirteen-time Canadian national team member, six-time national 1500-meter champion, and 1980 Olympic qualifier who couldn't compete due to the Moscow boycott.

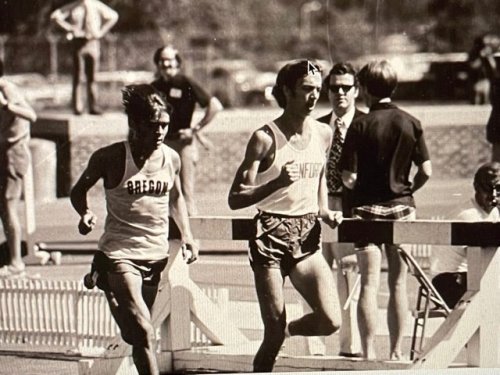

Dave Hinz—a 2:12 marathoner who'd competed in the 1984 Olympic Marathon Trials alongside champions Bill Rodgers and Greg Meyer.

These weren't weekend warriors. These were athletes who'd proven themselves on the world's biggest stages.

Over the years, the Ultimate Runner would attract other legendary names—Don Kardong, a fourth-place Olympic marathon finisher, would compete one year. Jeff Galloway, Olympic runner and famous author, would attempt it again the next year. Both had something to say about the race. See their comments in the images below.

But on this particular day in 1985, I wasn't on anyone's radar to win. A nationally ranked miler in my late twenties with aging legs, I was looking for one last challenge before retirement. My race number—11—roughly represented the officials' expectations.

Nobody expected what would happen next.

My Theory: Milers Were the Answer

I'd spent months thinking about this question: Who really is the most versatile runner?

And I kept coming back to the same conclusion: it had to be a miler.

Think about it. Milers need both strength and speed. You can't run a competitive mile without raw speed—the kind sprinters possess. But you also can't sustain mile pace for four laps without endurance—the kind distance runners build.

The mile sits at the perfect intersection. Fast enough to require explosive power. Long enough to demand aerobic capacity.

A pure sprinter couldn't handle a mile. A pure marathoner couldn't keep up with the speed.

But a miler? A miler could do both.

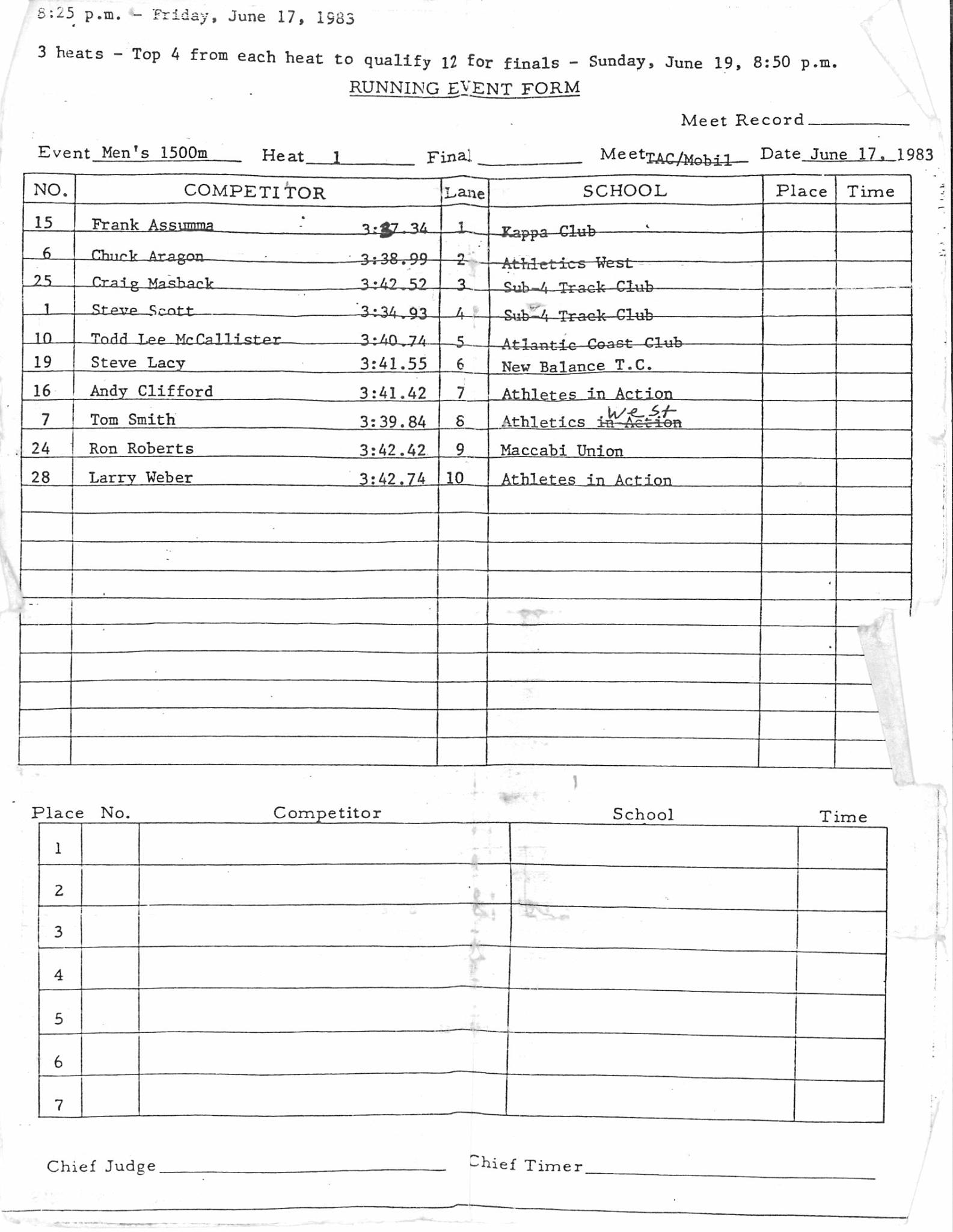

I'd competed at the USA Track and Field Championships in the 1500 meters against Olympians like Steve Scott and Steve Lacy, and 3:52 miler Craig Masback. I knew what elite middle-distance running required. And if the best all-around runner was going to be a miler, then maybe—just maybe—I had a shot.

Training on a Blank Piece of Paper

The problem was simple: I had no idea how to train for this.

There was no blueprint. No established program. No coach I could call who'd prepared athletes for five races in one day.

So, I sat down at my kitchen table with a blank piece of paper and started figuring it out myself.

How do you train for five races in one day?

Conventional wisdom said you couldn't do that, the body couldn't handle that kind of volume and intensity. Attempting to be good at sprinting and marathoning simultaneously would make you mediocre at both.

But what if conventional wisdom was wrong?

I started sketching out ideas—long runs to build an aerobic base, speed work to develop fast-twitch capacity. Tempo runs at lactate threshold to improve efficiency.

And then something clicked: lactate threshold training.

Most runners in that era trained either slowly (easy distance) or fast (intervals). But there was a middle zone—roughly half-marathon pace—where the body learned to process lactate more efficiently. Training at that pace built endurance without destroying speed.

What if I made lactate threshold work the foundation? Long tempo runs at half-marathon pace, combined with sprint work for the 400 and 100, and long slow distance for the marathon.

It was unconventional at that time. Unproven. Possibly stupid.

But it made sense to me.

I didn't have credentials. I'd trained under excellent coaches and competed at the national levels, but I had no coaching certification or degree in exercise science.

And I'd learned something important: results matter more than credentials. What works, works.

So, I started training. Alone.

The workouts were brutal. Long tempo runs that hurt but didn't destroy. Sprint intervals to maintain top-end speed. 20-milers to build marathon endurance. Combination workouts that simulated racing multiple events in one day.

My body rebelled at first. But slowly—week by week, month by month—adaptations happened.

I got faster at threshold pace. Stronger in sprints. More resilient over distance.

In May, I tested the training at the Main Street Mile in Olympia—a super-fast certified course. I ran 3:52.1. I had a track PR of 4:00.10 from 1983, barely missing a sub-four-mile, an event I rarely ever ran, so I was pleased.

Proof that the training wasn't destroying my speed.

Then, in February of that year, I competed in the KOY Classic 10K road race in Phoenix. I ran 29:34 on a certified course, finishing behind others like Bill Rodgers, a multiple Boston Marathon winner, by about 25 seconds.

Not a world-class 10k time, but a solid national road race time. Evidence that I could handle distance while maintaining speed.

The training was working.

But the real test was still ahead.

The Physiological Gauntlet: Race by Race

To understand why the Ultimate Runner was uniquely brutal, you have to understand what the human body goes through when forced to race—not jog, but race—across every distance from 100 meters to 26.2 miles in a single day.

Race 1: The 10K (Morning)

The Physiological Demand: Running 6.2 miles at race pace (roughly 85-90% of VO₂ max) immediately begins depleting muscle glycogen stores. My aerobic system was fully engaged, heart rate elevated, and my body was already beginning the process of glycogen depletion that would become critical later.

I ran conservatively, finishing fourth while the ultrarunners hammered the early pace. Smart strategy—but the damage was already beginning.

Recovery time: One hour.

One hour to partially restore phosphocreatine stores, clear some lactate, hydrate, and mentally prepare for the complete opposite physiological demand: an all-out sprint.

Race 2: The 400 Meters

The Physiological Demand: Here, the event's unique brutality becomes clear. The 400 meters is an anaerobic nightmare—a race that floods the body with lactate at levels approaching 12-15 mmol/L (normal resting levels are around 1-2 mmol/L). Heart rate spikes to 100% of maximum. The ATP-PC system (the body's immediate energy source) gets hammered. Muscle fibers begin accumulating damage that will compound throughout the day.

Now imagine running it after a 10K, with only an hour of recovery, and knowing you still have three races to go.

I lined up next to John Craig, the Olympic 1500-meter qualifier. Two middle-distance specialists are going head-to-head in the sprint that separates contenders from pretenders.

The gun fired.

I edged him at the line—first place.

I'd beaten an Olympian in the 400 meters after running 10,000 meters an hour earlier. My legs should have been trashed. Instead, the conservative 10K strategy had paid off—I still had reserves.

But the physiological cost was mounting. Lactate is flooding my system. Muscle fiber damage begins. Nervous system fatigue is setting in.

Recovery: Minimal

Race 3: The 100 Meters (The Wet Sweats Incident)

The Physiological Demand: Pure anaerobic alactic power—the ATP-PC system pushed to its absolute limit. This is explosive, maximum-effort sprinting that requires completely fresh neuromuscular coordination. Except mine wasn't fresh. It was carrying the cumulative fatigue of 10,600 meters of racing.

I went to the staging area and discovered a problem: my sweats were soaking wet—from rain, humidity, or sweat, I couldn't tell. The drawstring was stuck in a knot I couldn't untie.

Officials were calling runners to the line.

I made a decision I can still barely believe: I ran in the wet sweats.

The weight was oppressive. The fabric clung to my legs, restricting my stride. For 50 meters, I fought against the absurdity of the situation.

But I didn't panic. Didn't let anxiety take over.

I just ran.

Somehow—impossibly—I finished second.

More muscle fiber damage. More nervous system depletion. More glycogen is burned.

Recovery: About an hour

Race 4: The Mile

The Physiological Demand: This is the race that sits at VO₂ max—the absolute ceiling of aerobic capacity. In a fresh state, the mile requires running at maximum oxygen uptake, with lactate levels climbing throughout. Heart rate stays at 95-100% of maximum for the entire race. It's the most demanding sustainable effort the human body can produce.

Except I wasn't fresh. I was carrying the accumulated damage of three previous races spanning the entire metabolic spectrum.

My legs were carrying the fatigue of three races. My body was operating at VO₂ max—maximum heart rate and lung capacity, oxygen uptake plateaued, but demand stayed impossibly high.

John Craig made his move with 600 meters to go, trying to break the field.

I stayed on his shoulder. 400 meters. 300. 200.

Final 100 meters.

With about 60 meters remaining, I made a decision that would define my entire day: I eased up.

Not because I couldn't match Craig's kick. But because there was still a marathon to run, and I needed to save that final burst of energy for mile 26, not meter 1540.

Craig won the mile. I finished second.

Craig had chosen to win the race. I had chosen to save a bit for the marathon to try to win the competition.

Glycogen stores are now severely depleted. Muscle damage is extensive. Nervous system fatigue is profound.

Recovery: Longer break before the marathon

Race 5: The Marathon (The Great Unknown)

The Physiological Reality: A typical marathoner spends months preparing for 26.2 miles. They taper their training for 2-3 weeks before race day, carb-load for several days to maximize glycogen stores (which can hold approximately 2,000 calories of stored energy), and start the race completely fresh.

I was starting a marathon with glycogen stores already severely depleted from four previous races. My muscles were damaged from the sprint efforts. My nervous system was fatigued from operating at maximum capacity for hours on end. And my metabolism had already shifted toward fat oxidation—a less efficient fuel source, especially at race pace.

This is physiologically equivalent to starting a marathon at "the wall"—that point around mile 20 where most marathoners hit glycogen depletion. Except I was starting there at mile 1.

I had never run a marathon before in my life.

I'd done 20-mile training runs, but 26.2 miles after four races? That was purely faith.

The lead pack went out at sub-2:20 marathon pace—exceptionally fast. Dave Hinz, the 2:12 marathoner, was leading them.

I let them go. Settled into my own rhythm. Comfortable. Sustainable.

Mile 5. Mile 10. Mile 15.

I was running alone now, the lead pack ahead, the field scattered behind. My body was burning fat as primary fuel—a metabolic state that produces about 5-10% less power than glycogen metabolism. Every mile was harder than it should have been because the tank had been emptying since the 10K that morning.

Mile 18. Mile 20. Mile 22.

Then I saw someone ahead. Slowing down.

Dave Hinz. The 2:12 marathoner who'd led the early pace had gone out too fast. The cumulative toll of four races had caught him.

As I passed, I called out: "You've got this, Dave. Keep going."

Not because I had to. But because we were all suffering together.

Mile 24. Mile 25.

My legs were getting heavier—every step hurt.

Mile 26.

I could see the best ultra runners in the world, Klecker, Trayer, and Feckner—already finished, watching me come in. I was close to Klecker and Feckner, but one of the best ultra runners of all time won the marathon portion by a comfortable margin.

I crossed the finish line.

And my legs gave out completely.

The Science of Why This Was the Toughest One-Day Event Ever

From a purely physiological standpoint, what I accomplished that day shouldn't have been possible.

Let me break down exactly why, using the science of exercise physiology:

The Three Energy Systems—All Maximally Taxed

The human body has three primary energy systems:

1. ATP-PC System (Anaerobic Alactic): Powers maximum-intensity efforts for 0-10 seconds. Used in the 100m sprint.

2. Anaerobic Glycolytic System: Powers high-intensity efforts for 10 seconds to 2 minutes. Produces lactate as a byproduct. Used heavily in the 400m.

3. Aerobic System: Powers sustained efforts beyond 2 minutes. Used in the mile, 10K, and marathon.

Most races test one, maybe two of these systems. The Ultimate Runner demanded maximum performance from all three—in succession—within a single day.

The Metabolic Demands: Race by Race

Here's what actually happened inside my body: Race Distance Pace/Intensity Primary Energy System Physiological Effect Impact on Later Races 10K 6.2 miles 85-90% VO₂ max Aerobic endurance Glycogen depletion begins; aerobic system fully engaged Reduced glycogen availability for all subsequent races.

400m Quarter mile Max sprint endurance Anaerobic glycolytic + aerobic crossover Lactate spikes to 12-15 mmol/L; muscle fiber damage; heart rate 100% max Muscles flooded with lactate; legs compromised; aerobic system must work harder in the next race.

100m Sprint 95-100% max speed ATP-PC system (anaerobic alactic) Explosive effort; high neuromuscular demand; rapid phosphocreatine depletion Nervous system fatigue; coordination compromised; cumulative muscle damage.

Mile 1600m VO₂ max effort Aerobic power at ceiling Maximum oxygen uptake; lactate continues rising despite aerobic demand Both aerobic and anaerobic systems are overtaxed; severe glycogen drain.

Marathon 26.2 miles 75-85% VO₂ max Aerobic endurance + fat metabolism Forced reliance on fat metabolism due to glycogen depletion; extensive muscle damage Starting at "the wall"—the point where most marathoners fail

Why This Was Uniquely Impossible

Unlike ultramarathons, ultra races (50K, 100 miles) are brutally long but require steady, submaximal effort (typically 60-75% VO₂ max). The body never enters severe oxygen debt. Lactate levels stay manageable. The aerobic system dominates throughout.

Unlike Ironman Triathlons: While extraordinarily demanding, Ironman events maintain sub-VO₂ max pacing throughout. Athletes never push into the severe lactate accumulation of a 400m sprint or the maximum oxygen uptake of a race-pace mile.

Unlike Decathlons: The decathlon tests multiple skills and includes rest periods between events. Most events don't require simultaneous maximum aerobic or anaerobic output.

The Ultimate Runner uniquely demanded:

- Maximum oxygen debt (400m sprint producing 12-15 mmol/L lactate)

- Maximum aerobic power (miles at VO₂ max ceiling)

- Maximum aerobic endurance (marathon in glycogen-depleted state)

- All at racing intensity—not training pace, not submaximal effort, but race pace

- All within 8-10 hours

The Glycogen Depletion Crisis

Here's what makes the marathon portion particularly brutal:

The human body can store approximately 2,000 calories of glycogen (about 500 grams) in muscles and the liver. A marathon typically requires 2,600-3,000 calories of energy.

This means even a fresh marathoner must shift to fat metabolism during the race—usually around mile 18-20, known as "hitting the wall."

But I'd already burned significant glycogen in four previous races:

- 10K: ~600-700 calories

- 400m: ~50-75 calories (but depletes high-quality glycogen)

- 100m: ~25-30 calories (again, depletes fast-twitch glycogen)

- Mile: ~100-120 calories

By the time I started the marathon, I'd already burned 775-925 calories of my 2,000-calorie glycogen reserve.

I was starting the marathon with roughly 60% of normal glycogen stores—physiologically equivalent to starting at mile 10-12 of a normal marathon.

This forced my body to rely more heavily on fat metabolism throughout, producing approximately 5-10% less power than glycogen metabolism would have provided. Every mile was harder than it needed to be.

The Cumulative Muscle Damage

Each race created micro-tears in muscle fibers. Normally, athletes recover for days or weeks between maximum efforts to allow repair.

I was stacking damage upon damage:

- Sprint efforts damaged fast-twitch fibers

- VO₂ max running damaged intermediate fibers

- Marathon running damaged slow-twitch fibers

By the final miles of the marathon, I was running on muscle tissue that had been systematically destroyed across the entire fiber-type spectrum.

The Nervous System Depletion

Maximum-intensity efforts (sprints, VO₂ max running) create profound nervous system fatigue—the brain's ability to recruit muscle fibers degrades with each successive effort.

By the marathon, my nervous system's capacity to coordinate efficient running mechanics was severely compromised. This explains why elite ultrarunners—who specialize in managing nervous system fatigue over extreme distances—still found the Ultimate Runner brutally difficult.

When officials tallied the final scores, the announcement came:

Winner: Larry Weber. The best all-around runner in the world.

I had set a new event record—a cumulative point total that would stand as the best in the competition's history. Better than the Olympic marathoners who would attempt it in other years. Better than the ultrarunning legends. Better than the middle-distance specialists.

The record still stands today.

What I Haven't Told You Until Now

I've written about the Ultimate Runner before. I've shared the basics—the five races, the jelly legs, the victory.

I once mentioned in passing, in an article I wrote about meaningful motivation, that I was running for someone else that day. But I never shared the full story in the original Ultimate Runner article.

Until now, I've never publicly revealed my primary motivation for competing that day.

Partly because it felt too personal. Too sacred. Too difficult to capture in words how much it meant.

But mostly because I didn't want to diminish it by making it sound like a motivational technique or a psychological strategy. It wasn't a trick I used to push harder.

It was the why behind everything.

A young family member with cystic fibrosis came to watch me race that day.

At the time, the life expectancy for someone with cystic fibrosis hovered in the late teens or early twenties. She was approaching that age. She knew it. Her family knew it. We all knew it, though we didn't talk about it directly.

Despite everything she faced—the constant struggle to breathe, the medical treatments, the limitations imposed by a disease she didn't choose and couldn't cure—she was one of the most joyful people I'd ever met.

She was excited to watch me race. Proud of me. Looking forward to it with an enthusiasm that both humbled me and terrified me.

Because I felt an overwhelming responsibility not to let her down.

She struggled to breathe on an ordinary day. Just sitting still required effort. Walking across a room could leave her winded.

And I had the privilege—the absolute, undeserved privilege—to run. To push my limits. To test what my body could do. To breathe freely, deeply, without thinking about it.

How dare I waste that gift?

How dare I hold back, conserve energy, protect myself from discomfort when she would have given anything to have what I took for granted every single day?

On that day in Michigan, standing at the starting line of the marathon after four previous races, I realized something with crystal clarity:

I wasn't racing for myself anymore.

I was racing for her.

For someone who couldn't run herself but who found joy in watching someone else push the limits of what the human body could do.

Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist who survived the Holocaust, observed something profound: "He who has a why can bear almost any how."

My why was sitting in the crowd, smiling, believing in me.

When you're running for yourself, you can quit. Your brain gives you a thousand rational reasons to stop when it hurts too much.

But when you're running for someone else—especially someone who can't run themselves—quitting becomes impossible.

Because it's not about you anymore.

When the miles got hard around mile 18, when my legs started to rebel, when my mind started suggesting I could slow down and still finish respectably—I thought about her.

About her struggling to breathe while I breathed freely.

About her limitations, while I tested mine.

About her joy in watching me do what she couldn't.

And I kept running.

When I passed the 2:12 marathoner who was walking at mile 22, when I realized I could actually win this thing, when I had to dig deeper than I'd ever dug before—I thought about her.

When the final miles should have broken me, when every muscle screamed for me to stop, when I had nothing left in my own tank—I thought about her.

And I found something I didn't know existed: a reservoir of strength that doesn't come from training, talent, or willpower.

It comes from love.

Love in action. Love that says, "I will suffer this so you can share in the joy of it." Love that transforms pain into offering.

The Breaking Point

After I crossed the finish line, after officials tallied the scores and announced I'd won, after they had to lift me onto the awards platform because my legs wouldn't work—I found her.

She was smiling. That beautiful, radiant smile that lit up her whole face.

And she hugged me.

I can still feel that hug decades later. Still remember exactly what it felt like. Still recall the overwhelming sense that this—this moment of connection, this expression of shared joy—meant more than anything I'd accomplished on the course.

The medal was just metal. The title was just words. The record was just numbers.

But that smile? That hug?

That was everything.

My legs had turned to jelly because I'd given everything—every ounce of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual strength.

The tank was beyond empty.

And sitting in that chair, unable to stand, I had a realization that would change everything:

I didn't do this.

The training had been good. The strategy had been smart. The execution had been near-perfect.

But none of that explained what had just happened.

The math didn't add up. My training—as good as it was—shouldn't have been enough. The blank piece of paper approach, the lactate threshold foundation, the combination workouts—all of it was sound, but it wasn't that good.

I wasn't strong enough for what I'd just accomplished.

Which meant something else had carried me. Someone else.

I thought about the prayer before the race. That simple, desperate plea: God, I need Your help. I can't do this on my own.

At the time, I didn't know if God cared about running races. Didn't know if prayer worked that way.

But sitting there with jelly legs, unable to stand, the evidence was undeniable:

I couldn't do it on my own.

I'd proven that definitively.

My strength had failed. Completely. Absolutely.

And yet I'd finished. And won.

Which meant the strength that carried me through wasn't mine.

There's a verse I'd heard before. Philippians 4:13.

"I can do all things through him who strengthens me."

I'd always interpreted it as: God helps me be stronger. God enhances my abilities. God makes me more capable.

But sitting in that chair, legs useless, unable to stand—I finally understood what it actually means.

It doesn't mean God makes you stronger.

It means God's strength works when yours runs out.

"I can do all things"—not through my training, not through my strategy, not through my mental toughness.

"Through him who strengthens me."

Not "with His help." Through Him.

When my strength completely failed—when there was literally nothing left—His strength didn't fail.

That verse became my life verse from that day forward.

Not because it promised I'd be strong enough for every challenge.

But because it promised something better: that when my strength fails, His doesn't.

From that day on, I've signed everything: Blessings, Coach Weber, Philippians 4:13.

Not as a signature. As a testimony.

The Aftermath

John Craig, the Olympic 1500-meter qualifier, said after the race that it was a great experience—but he would never do it again. It was too physically demanding.

Dave Hinz, the 2:12 marathoner, agreed.

Don Kardong would compete in a different year, finishing fifth, and describe passing a dead raccoon in the marathon's final miles: "I thought the roadkill looked better than I felt."

Jeff Galloway would attempt it again the next year and compare it to his Vietnam experience.

These were world-class athletes, Olympians, saying the Ultimate Runner was the hardest thing they'd ever done. That once was enough.

But surprisingly, none of them—not Kardong, not Galloway, not any competitor across all the years the event was held—would surpass my all-time point total.

My legs didn't fully recover for months. Two months later, at the USA Cross Country Championships, I was still feeling the effects.

But the experience changed me permanently.

I went on to coach for 15 seasons, winning 13 Washington State Cross Country Championships. I coached Paralympic gold medalists like Tony Volpentest, who won two gold medals and set a world record under my guidance. I coached Olympic Marathon Trials qualifiers like Karen Steen. And I coached countless teenagers who discovered capabilities they didn't know they had.

In January 2026, I was inducted into the Washington State Coaches Cross Country Hall of Fame.

Every athlete I've ever coached has heard this story. Not to impress them with what I accomplished, but to teach them what I learned:

You will reach the end of your strength. That's guaranteed.

And that's exactly the point.

Because the breaking point—the moment when human strength ends—is where you meet God. Not in theory. Not in Sunday school. But in desperate, absolute, undeniable dependence.

Why I'm Telling the Full Story Now

I've kept parts of this story close for nearly four decades.

The young family member with cystic fibrosis passed away years ago. The disease that shadowed her entire life eventually claimed her, as we all knew it would.

But the memory of that smile, that hug, that moment of pure joy—it's more meaningful to me than any medal or title I ever earned.

Because it taught me what my gift was actually for.

Not for my own glory. Not for my own satisfaction. Not even for my own sense of accomplishment.

But for others. For the people who couldn't do what I could do. For the ones struggling with burdens I'd never carry.

Running became something different after that day. Something sacred. Something I couldn't take lightly because I knew it was a privilege not everyone had.

Every time I laced up my shoes, I was running for her. For everyone who'd wanted to run but couldn't. For all the people whose bodies betrayed them in ways mine hadn't.

That's what transformed running from an idol into a calling.

And that's why I coach the way I do—always looking for the kid who doesn't yet know what they're capable of, always believing in potential others can't see, always remembering that every gift we have is meant to be given in service of others.

Serve and love others; it’s that simple.

The Question That Remains

The Original Ultimate Runner Competition no longer exists. The event that once attracted Olympians and national champions faded into obscurity.

But the question it tried to answer still resonates:

What are human beings truly capable of when pushed to absolute limits?

The physiological data is clear: I accomplished something that shouldn't have been possible—racing at maximal intensity across every energy system in a single day.

No other event in history has demanded:

- Severe oxygen debt (400m producing 12-15 mmol/L lactate)

- Maximum aerobic power (miles at VO₂ max ceiling)

- Glycogen-depleted marathon endurance (starting 60% depleted)

- All at racing intensity within 8-10 hours

The competitors' testimonies confirm it—Olympians across multiple years calling it the hardest thing they'd ever done.

And my own experience reveals a deeper truth: sometimes the breaking point isn't the end of the story. It's where the real story begins.

Because that's where you discover what you're made of when everything else is stripped away.

That's where you meet something—or Someone—carrying you when you can't carry yourself.

That's where jelly legs become testimony.

And that's why, nearly four decades later, the day I couldn't stand on my own remains the most important victory of my life.

My Ultimate Runner Competition record still stands as the best all-time point total in the event's history. No one—across all the years it was held—ever surpassed my cumulative performance across all five races in a single day. I'm sharing this more detailed version of the story now—including the physiological breakdown and the motivation I've mentioned only once before in a different context—because I believe the lessons I learned that day about purpose, sacrifice, and discovering strength beyond our own selves matter more than ever when serving others.

Blessings,

Coach Weber

Philippians 4:13

Race number 11—roughly where officials expected me to finish. To my left: 2:12 marathoner Dave Hinz. In the field: American 50-mile record holder Barney Klecker, Ultra Running Hall of Famers Charlie Trayer and Stefan Feckner, and Olympic qualifier John Craig. Nobody expected the miler to win."

Barney Klecker participated in the Original Ultimate Runner Competition and held the American record for 50 miles for nearly 40 years. His son, Joe Klecker, was on the 2021 Olympic Team in the 10,000 meters event, while his wife, Janis, was a member of the USA Women's Olympic Marathon team.

Barney is in the American Ultra Runners Hall of Fame here: Barney Klecker – 2010 Hall of Fame Member | Ultrarunning History

Photo Credit is unknown.

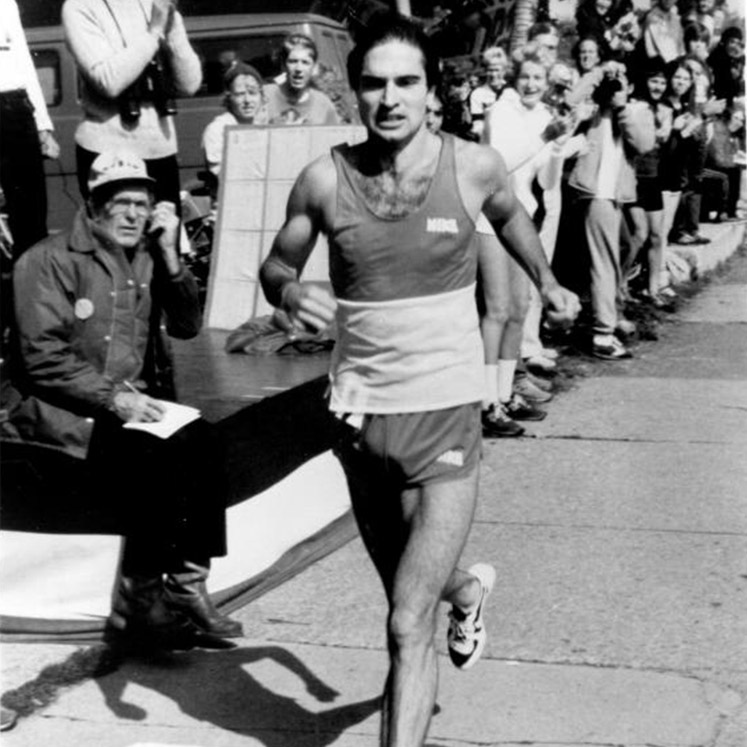

John Craig (1500-meter Olympic team qualifier, Multiple Canadian National 1500-meter champion, National Road racing champion)

Image Credit: CP Photo/COA)

Dave Hinz 2:12 marathon runner grimacing at the race

Image Credit: Jackson Citizen Patriot

Dave Hinz is seen running in the lead pack of the 1984 USA Olympic Marathon Trials, positioned right behind Dave Gordon, number 10. He is also running alongside Boston Marathon champions Bill Rodgers and Greg Meyer. With a remarkable marathon time of 2:12, Dave Hinz was an exceptional athlete and great man. Tragically, he passed away at a young age in an auto accident.

Legendary runner and coach Jeff Galloway (also pictured with Prefontaine) would attempt it another year, comparing it to his Vietnam experience in jest.

Photo Credit Unknown.

Olympic marathoner Don Kardong (pictured here racing Steve Prefontaine) would compete in the Ultimate Runner a different year, finishing fifth. He later said: 'I thought the roadkill looked better than I felt.

Photo Credit: Original Gangsters Of Running (Don Kardong) – JDW

www.jackdogwelsh.com

Charlie Trayer, number 8, and Stephen Feckner, also number 8, are competing in the Original Ultimate Runner Competition. Both went on to become Hall of Fame ultramarathon runners. Trayer earned the nickname “Grandfather of American Ultra Running” for his groundbreaking achievements in the sport.

Read about his amazing career here: Charlie Trayer: 1980s Ultrarunning Legend | Ultrarunning History

Image Credit: Original Ultimate Runner Promotion Brochure

My heat sheet before we ran at the semi-finals at USA Track and Field Championships (called the TAC Track and Field Championships back then) with American Mile Record Holder and Olympian Steve Scott, Olympian Steve Lacy, and 3: 52 miler Craig Masback who later became CEO of USA Track and Field.

My main event was the mile and so was John Craig's. Milers went 1-2 the year I won and set the all-time record in the event.

I was blessed to win the overall title of the Ultimate Runner, setting a new point total record that was never been broken.

Image Credit: Ultimate Runner Race Organizers